The Decision-Making Conundrum

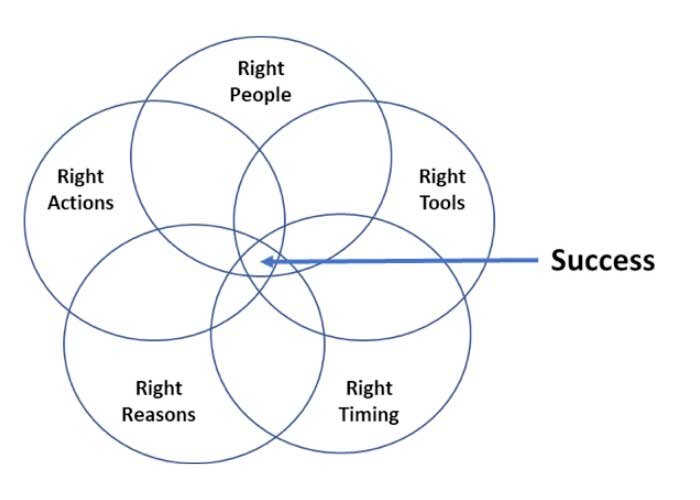

Before we answer the previous question and the process of great decision-making, it is important for us to understand the components of the decision-making process itself. To do so we need to decompose the decision-making from “end to end”. To some extent or another, all leaders make decisions based on data. They are given data that requires indicates to them that they have a choice to make. Leaders are expected to be knowledgeable in their areas of expertise and control. Most of all leaders also possess a “sense of urgency” that, when not taken in the proper context, can lead to poor decisions. The true focus of great decision is making decisions that are focused on right and not necessarily on “fast”. In any case, it is important to consider a review of my “perfect storm” of success (another discussion). Yet for the sake of this discussion let us review the 5 “Rights” or components of successful decision-making. They are:

The Right People. Doing

The Right Things. At

The Right Time. For

The Right Reasons. With

The Right Tools.

For those who are more visual than verbal, successful decision-making looks like:

Interestingly, results always occur at the intersection of these 5 components. If one or more of the 5 components are inadequate, that decision and the following activities will result in less be less than desired. Successful results most often occur when each of those 5 components are considered in relation to their contribution to success and properly blended into a single effort. Successful decision-making is not a skill that is simply driven by knowledge and behavior.

Successful decision-making is highly dependent on data. Decisions made unsupported with data are simply guesses and open to chance. Assuming that decision-making is done based on data, there are two general sources from which the data is obtained. It is either 1) experiential (based on similar experiences from the past) or 2) some type of data captured analysis related to the current situation.

Data is the beginning of the decision-making process. Unused, it simply remains data. When data is retained for future use or is used, it becomes knowledge. This leads us to the notion of knowledge. Knowledge is simply the data possessed in relation to the situation being addressed or that will be addressed. The more that the data matches reality the more accurate it is. The more data that an individual possesses for that situation, the more knowledgeable they can be considered. What is often ignored in every situation is that the fact that data is always incomplete. To paraphrase the philosopher Socrates, who once said, “The more I learn, the more I realize what I do not know.” It is nearly impossible to capture or possess the entire population of data. This adds another question to our discussion, “When does stop gathering data before the decision is made?” Interestingly, the answer is somewhat embedded within that question!

Putting Data in its

“Leaders in process” often fall prey to a common decision-making challenge called “analysis paralysis.” Analysis paralysis occurs when a leader gathers data, questions the validity of the results of the analysis and continues to analyze the situation, ad infinitum. There are numerous reasons for this occurring, but the fact is, there is a time for data collection and analysis to stop. I have an axion that I live by. It says, “If you find yourself in a position that you have to make a decision, you do not have enough or the right data.” Every decision is a proverbial “crossroad”. One can choose to travel left, or one can decide to travel right. Only one of the directions taken is correct. The correct choice may not be apparent immediately. In fact, the choice may appear totally the same, but the road may be rough or impassible at the first bend in one and not the other. Data collection and analysis should cease when ne option is eliminated.

Let us continue that analogy a bit deeper. The process of decision-making is an understanding the equation Y=f(x), which verbally is, “output (Y) is a function of the inputs (X’s).” This is simply a nice way to represent the Cause/Effect relationship. Which leads us to an interesting insight. The decision is the output of the decision-making process. Data is one of the X’s

When a leader is confronted with the need for a decision, which is the result of data and that data is combined with evaluative criteria, it results in an awareness of a condition or situation which is an unwanted result or output of a process. Often many tend to focus on the process that needs to be changed and ignores the process that they are using to make those decisions. Let us consider the categories in which a leader’s decisions can be placed. They are four types of leadership decisions related to the output of a process. They are decisions related to output time, volume, quality, or cost. The bottom-line is that regardless of the decision, it is about a change related one of those elements. Decision-making assumes that something must change. Something needs to happen. It is either that is must happen more frequently or that it has to happen less, or it needs to not happen at all. This is the general construct of the requirements related to the decision-making process.

Changing what Matters

Returning the Y=f(X) equation, to affect that change, something must happen in the “X” side of this equation. Although the Y is the indicator of the problem, it is too late to fix t by the time that it becomes a “Y”. Remember that any issue or problem requiring change is an output from some unintended combination. The general categories include presence, content, sequence, and composition. This. Is simple control of the Cause/Effect equation. Change the “X” to provide the “Y” as it was intended.

Returning to a previous thought, if a leader is confronted with a situation that does not meet output needs, or standards, and he had experienced prior to this event, he will likely make a series of decisions and based on that experience and rightly so, because this is also data. This is what is known as experiential knowledge. Cutting to the chase, knowledge of the Cause/Effect situation is data and often the basis for decisions. Again, this takes us full circle to answering the question, “What is successful leadership in relation to decision-making?” The answer is simple. It is “wisdom”.

From there, this leads to the next question, “What is wisdom?” The simple answer is,” Wisdom is providing the right answer…” and this takes us to the need for an understanding of the meaning of “Right”.

It is a Matter of Consequence

On the surface, the right answer or decision is one that meets the needs of those that it effects. Going back to a previous insight, every decision contains some type of change. Every change has inherent costs and benefits. Practically speaking, to be “the “right” decision, the benefits must outweigh the cost. This then leads to the following question, “What is the timeframe that one must consider duration to fully realize the true “rightness” of the decision?” The short answer is, “It depends!” “Rightness” or value timeframes can be limited to the immediate moment or a short-term or a long-term impact. In every situation there are different costs and different benefits thus “rightness” is tied to the net effect of any given period. This must also be considered in the decision-making process.

This leads us to a discussion related to cost and benefit “rightness” and its relation to intended consequences. Often, the intended, value-added, consequences are offset by being blind-sided by that which was not anticipated. Let us call these “unintended consequences”. Great leaders, who possess wisdom, intuitively understand the impact of the Cause/Effect/Impact equation. They consider the net effect of the intended consequences (both benefits and detriments) and the risk related to unintended consequences. There are many tools and techniques that can aid in the identification of unintended consequences, one of which is the Failure Modes Effect Analysis or FMEA. This tool decomposes a process into its input components and the risk related to each. With a slight modification, this tool can be used to identify decision weaknesses and allow for more successful decisions. Rather than conducting a FMEA, a great leader has an FMEA mindset that supports an entirely different view of decision-making. This is what the Cii guides leaders to do.

It is apparent that sound leadership decision-making is complex. It is not simple and prone to error. Regardless, this is a necessary aspect of true leadership. Requiring this of a leader may sound like having unrealistic expectations. If an organization does not demand this of leadership, it may be that the proverbial “bar” is set too low. Wisdom is essential, and companies cannot thrive without it. If one aspires to be a true leader, this is a characteristic that needs to be pursued. Leadership is not just about what an individual knows, or the ability to decide, but to make the best decision, the wise decision that not only considers “Cause/Effect, it embeds “Impact” into it also. That is the “wise”.